AL9 — Anis Mojgani’s Radical Empathy

OREGON | In conversation with the Poet Laureate of Oregon

WORDS BY MILES FORRESTER

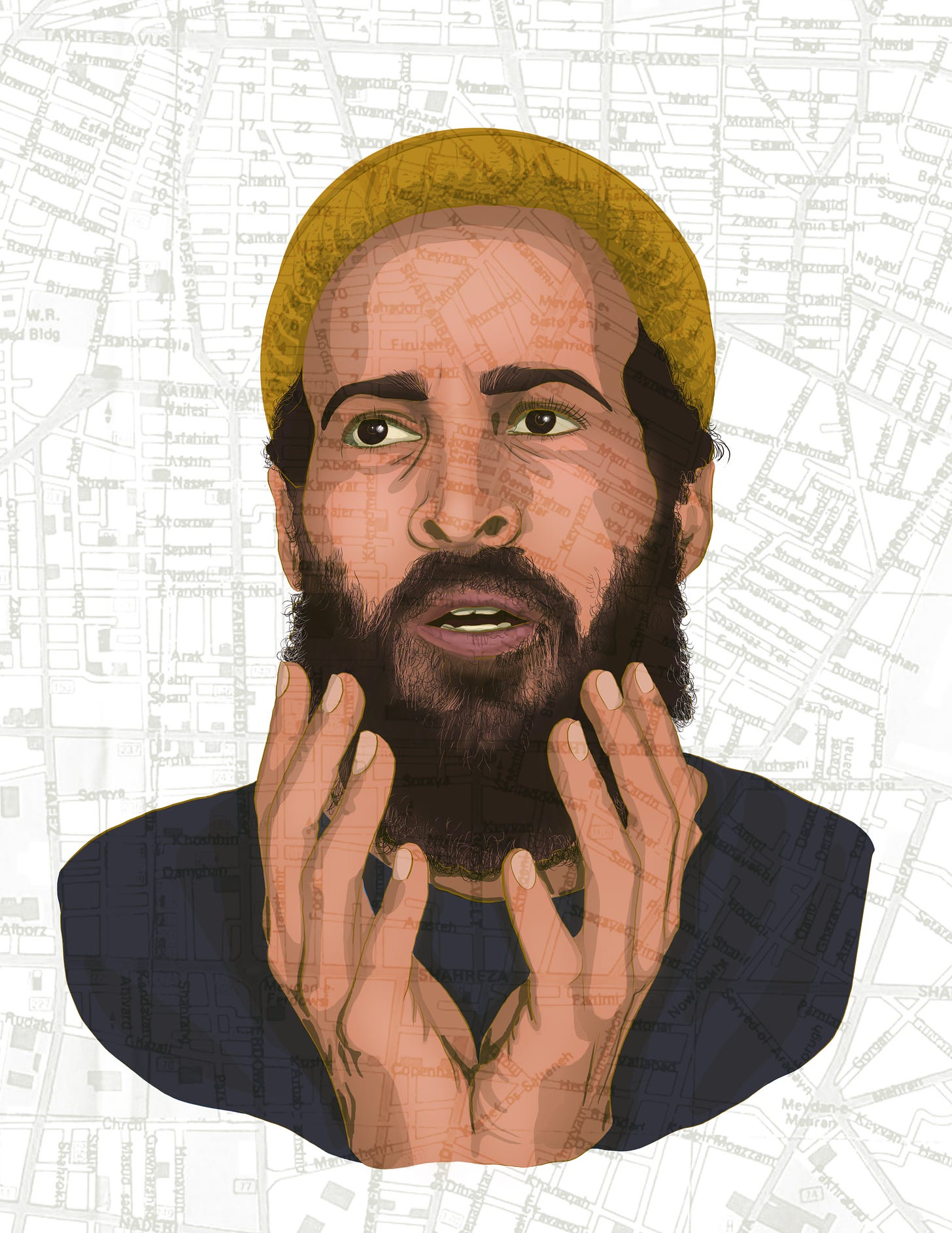

ILLUSTRATION BY ELLA MAZUR

Over Anis Mojgani's shoulder, a “Black Lives Rule” poster hangs in the Zoom frame. The Poet Laureate of Oregon designed it in collaboration with musician Laura Veirs and her young son (he created the initial drawing) to fundraise for the Portland General Defence Committee and other BLM organisations. With poems like “Shake the Dust” and “Direct Orders” — performed on stage with his uniquely spirited delivery — Mojgani has amassed an enthusiastic following over the last two decades. His prowess on and off stage has made him a winner of both national and international Poetry Slam competitions and the author of six books of poetry. When Mojgani talks about poetry, it takes a second to realise that he’s not describing a literary form, but a vital force. He regularly uses language related to cultivation in conversation: his sentences are rife with blossoms, stems, and roots. The Piano Farm (his website) describes the metonymic space for his endeavours. It began as a humble non-sequitur he misheard from a friend while attending the Savannah College of Art and Design. Although the initial short story it inspired remains unfinished, his connection between farming and poesis remains inextricably linked, maintaining that “making art is a combination of what is intangible and ethereal — connected to the imagination that we no control over — and, also, it’s very much connected to a specific path of intent, process, and science.”

For Mojgani, the presence of “poetry” doesn’t necessarily cohere into a poem, which makes sense, not only because he’s a multi-hyphenate artist — his creative output includes written poetry, illustrations, and electrifying performances — but it also reflects how he grounds himself in the paradoxes of faith, race, and nationality. Mojgani joined Cannopy on the occasion of his latest poetry collection, The Tigers, They Let Me, released 2023. Informed by Kenneth Rexroth’s translations of Chinese poetry and the Andalusian poet and playwright, Federico Garcia Lorca, this volume synthesises many of the themes that he explores in this discussion: the intimacy and contradictions of presence and absence. This year, Holiday House/Neal Porter Books published Mojgani’s first children’s book, Lifespan of a Rock. Told from the point of view of a nephew collecting and tossing rocks with an uncle, it explores similar themes as Tigers, They Let Me, being simultaneously in and out, both and neither, “the weights of people that we carry, even if they’re no longer with us.”

CAN | How do you hope your role as Poet Laureate will serve the literary life of Oregonians?

AM ── When folks are asking, “What is your role? What do you do?” I’ve tended to define it as serving as a steward, an ambassador, to and for “poetry” and the people of Oregon. For me, that entails trying to see avenues by which I can foster, introduce, develop, and strengthen — depending on the scenario, depending on the person, depending on the community — an ongoing relationship with poetry.

I think it’s less about poetry in the realm of a very concrete definition of a “poet.” Like, “poetry” exists within the shape of a poem; there are all these parameters — and boundaries that don’t exist — of what a poem is. Moreso, if “poetry” is the root of the poem, I’m interested in what our relationship to the poetry is. What is our relationship to seeing and engaging with the “poetry” existing around us in our everyday life, even if they never find their way to becoming an actual poem? I think the purpose of a poem is to move and connect us to something larger than our parameters, however we arrive there. Whether it’s by writing and reading poems or simply being observant — to ourselves, to the people around us, and to the world that we’re moving through — “poetry” constantly communicates with us by way of the unseen world.

CAN | Your poetry is very performative, almost musical. But The Pocketknife Bible (2015) combines visual and performative elements. How do you enjoy the friction between those different languages?

AM ── It’s like how you phrase it, they’re different languages. If you ask “which way to the library” in English, Spanish, and Russian, the intent's the same─but it’s not going to sound the same, and it’s going to have different etymologies. To me it feels very much like that. They’re all bubbling up from the same place in me. I think the different things I explore creatively all seek to unravel more and more questions for myself.

How do we rectify our interior self in an exterior environment? How do we rectify the exterior life that we live while engaging with an interior universe? All these mediums are ultimately trying to unpack that, lending themselves, at least for me, to what’s most appropriate to their characteristics. My visual work seeks to do the same thing, but in a very different way — and through different questions — what my poems seek to do. Same thing with the performative aspect. All these elements are the same thing, but they’re coming at it differently.

Sometimes there’s a thing that I want to deliver by way of a poem — or by way of a picture, a painting, a song — and I don’t have the tool for it, the skill for it, the roadmap. So, it has to happen by way of something else. There’s, at times, that friction of wanting to do it this way, but it has to be translated by way of that. It might be the flip; where I think that it’s supposed to be a picture, but as I’m working on it, I realise, “oh, what this actually wants to be and needs to be is something else.” They work hand in hand. I don’t think they work in opposition to each other.

CAN | As a Persian-American of the Baháʼí Faith, how are you processing the ongoing protests in Iran?

AM ── My hope is that the oppression will cease, will just dissolve, not simply in Iran, but the globe over. Time and time again, we see these structures of government─here in America, everywhere. There’s a want and a love and a fervour wrapped up with a worry and a loss and a frustration. Will it cross this threshold? I still haven’t figured out the succinct language of all that I’ve been feeling.

My relationship to Iran is one of such distance, growing up in a household that was mixed. We existed in our own orbit. I don’t think that I’m alone in that. All diasporas have very specific effects on the individual, but it falls under the same balloon. What’s an individual’s relationship to what they have come from if they haven’t come from it?

So the protests have been weird and challenging. My heart breaks for this. At the same time, there’s this confusion. Where was the voice and support 20 or 60 years ago for the Baháʼís? I’ve never been able to go to Iran because Baháʼís are persecuted there. I can’t go see the place that my father was raised in. There’s, at times, a saltiness that I want to acknowledge while, also, a saltiness that I don’t want to hold onto. It’s like the same thing I thought about when the Black Lives Matter protests were happening two summers ago. Of course, I want whatever’s going to get us across the finish line. I want that. But it’s frustrating, when Black women experience the basest horrors in our society, it’s not until a person of a different shade experiences the same thing that the larger populace start focusing on it.

How do we, as a culture, speak for the people while also speaking against the government? Not conflating those things becomes tricky. If we’re speaking against the oppression of brown people by a government of brown people, what are other countries and governments that we aren’t speaking up against? Where do we fit the conversation of Israel and Palestine, of India and Pakistan? You start dealing with these frustrations that take up space and time into yourself, away from what’s at the heart of the matter. My hope is that more folks around the planet will bear witness to what’s happening there. How might bearing witness be quantified into action? This question applies to Iran specifically, but also to oppressions elsewhere.

CAN | Looking back at your poem, ”Shake the Dust,” how do you stay loyal to that poem’s radical empathy?

AM ── I try to remain loyal to radical empathy by recognizing that I haven’t attained that which I desire to attain. Empathy’s purpose isn’t for me to feel good: “Oh, I did it. I feel you. Peace out!” It’s a tool to move further. I think of how the conversation on radical empathy has changed, or strengthened, by being more cognizant of what it is and the walls that keep us from it. I wrote “Shake the Dust,” I don’t know, 25 years ago. I can’t speak to all the ins and outs of writing it from this juncture, I wasn’t quite sure what it meant. There’s this aspect of Baháʼí philosophy, that we are all born invested with nobility. Not to say that we aren’t capable of monstrous things. But we’re all noble creatures. How do we retain that nobility? How do we return to that nobility? How do we foster and blossom it even larger─even when we have sought to kill it at the roots?

That poem stems from that. But in the years since then — (Laughs) give me the slightest cracked door to talk about capitalism and I’ll just go off! — so much of the plight of empathy is rooted in what capitalism is rooted in. Here, in the States, we’re continually required to look at something as being right or wrong, good or bad. That aids the capitalist machine. It’s rooted in competition: scarcity versus abundance. Being introduced to those ideas has allowed me to strengthen down on the real things keeping us from being empathetic over the course of our entire lives.

We’re also all wrestling with the fact that we’re all alone. We’re alone in ourselves. We’re alone in our thoughts. When we pass this world, it will be just us going to the next thing or nothing. So how do we bridge that? The best way is this vulnerability, which engages us with each other. One of the tools is empathy. So saying we’re only the sum of our worst-ness or best-ness doesn’t fly with me. The last 15 years or so, I’ve become more privy to that language, aiding my loyalty to radical empathy.